Léonie de Jonge, University of Tübingen and Rolf Frankenberger, University of Tübingen

The far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) looks set to become the second largest party in the German parliament following elections on February 23. Polls ahead of the election and an exit poll suggest they could receive around 20% of the final vote tally. For the first time, the AfD poses a challenge to mainstream parties’ longstanding strategy of isolating the far right.

The rise of the AfD is striking, given the country’s history of authoritarianism and National Socialism during the 1930s and 1940s. For decades, far-right movements were generally stigmatised and treated as pariahs. Political elites, mainstream parties, the media and civil society effectively marginalised the far right and limited its electoral prospects.

The AfD’s breakthrough in the 2017 federal election shattered this status quo. Winning 12.6% of the vote and securing 94 Bundestag seats, it became Germany’s third-largest party — unlocking viable political space to the right of the centre-right party CDU/CSU for the first time in the postwar era.

Want more politics coverage from academic experts? Every week, we bring you informed analysis of developments in government and fact check the claims being made.

Sign up for our weekly politics newsletter, delivered every Friday.

The AfD was founded in 2013 by disaffected CDU members. This included economics professors Bernd Lucke and Joachim Starbatty, and conservative journalists Konrad Adam and Alexander Gauland. It began as a single-issue, anti-euro party advocating Germany’s exit from the Eurozone.

Dubbed a “party of professors”, it gained credibility through the support of academics and former mainstream politicians, lending it an “unusual gravitas” for a protest party. While nativist elements were arguably present from the start, the AfD was not initially conceived as a far-right party.

When it first ran for the Bundestag in 2013, its four-page manifesto focused exclusively on dissolving the Eurozone. At the time, the party advocated political asylum for the persecuted and avoided harsh anti-immigrant or anti-Islam rhetoric, cultivating more of a “bourgeois” image.

This helped the AfD build what political scientist Elisabeth Ivarsflaten has called a reputational shield — a legacy used to deflect social stigma and accusations of extremism.

Initially, the AfD distanced itself from far-right parties in neighbouring countries. However, successive leadership changes between 2015 and 2017 saw the party adopt a more hardline position, particularly on immigration, Islam and national identity. By 2016, its platform had largely aligned with those of populist radical right parties elsewhere.

Far-right views

Today, the party can unequivocally be classified as far right. This umbrella term captures the growing links between “(populist) radical right” (illiberal-democratic) and “extreme right” (anti-democratic) parties and movements. Ideologically, the far right is characterised by nativism and authoritarianism.

Nativism is a xenophobic form of nationalism, which holds that non-native elements form a threat to the homogeneous nation-state. In Germany, nativism carries a historical legacy. “Völkisch nationalism” was one of the core ideas of the 19th and early 20th centuries that was broadly adopted by National Socialism to justify deportations and, ultimately, the Holocaust.

Völkisch ideology is based on the essentialist idea that the German people are inextricably connected to the soil. Thus, other people cannot be part of the völkisch community.

The AfD has evolved into a far-right party by continuously radicalising its positions. It acted like a Trojan horse, importing völkisch nationalist ideology into the parliamentary and public arena, which used to be blocked by the gatekeeping mechanisms of German democracy.

The AfD carved out a niche for itself by advocating stricter anti-immigration policies. This came in response to the so-called “refugee crisis”, when then-Chancellor Angela Merkel welcomed more than a million asylum seekers into Germany. At its campaign kickoff rally in January 2025, AfD’s chancellor candidate Alice Weidel vowed to implement “large-scale repatriations” (or “remigration”) of immigrants.

The party advocates a return to a blood-based citizenship, insisting that, with very few exceptions for well-assimilated migrants, citizenship can only be determined by ancestry and bloodline rather than birthright.

Additionally, the party upholds the white, nuclear family as an ideal and has pledged to dismiss university professors accused of promoting “leftist, woke gender ideology”. The party also calls for the immediate lifting of sanctions against Russia and opposes weapons deliveries to Ukraine.

In recent years, the party has embraced the far-right strategy of flooding the media and public discourse with controversy, misinformation and inflammatory rhetoric, to dominate attention and transgress traditional political norms.

A striking example is former AfD-leader Alexander Gauland’s 2018 claim that the 12 years of Nazi rule were “mere bird shit in over 1,000 years of successful German history”. With this remark, he sought to reframe modern Germany as a continuation of its pre-1933 history, while downplaying the significance of the Nazi era.

Normalising the AfD

Until recently, the far right was consistently excluded by mainstream political parties. It was a founding myth of the old Federal Republic of Germany that democratic forces do not cooperate with the far right. At least on the parliamentary level, this worked quite well as a part of Germany’s “militant democracy”.

However, the political firewall — the Brandmauer — has started to crumble. The AfD has since celebrated the election of its first mayors at the local level.

The success of the AfD has especially been fuelled by the narrative of a “refugee crisis” in Germany. Harsh political rhetoric about migration has contributed to the party’s electoral success, as well as mainstream adoption of some of its positions.

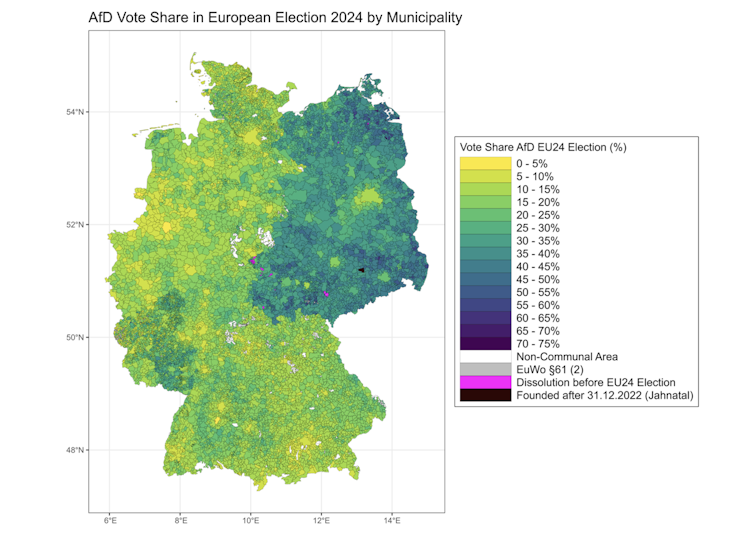

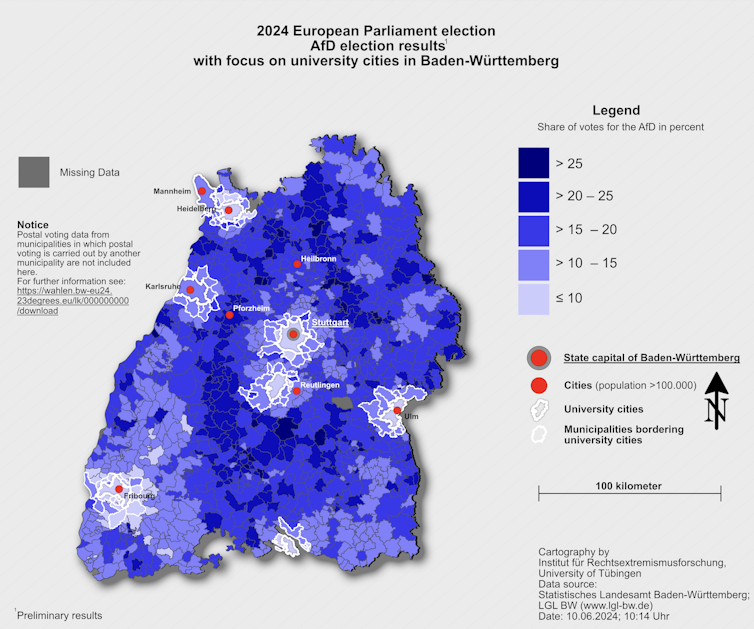

Oddly enough, the AfD is especially successful in rural, remote areas with low levels of migration. It is weak in more globalised, university-oriented urban areas.

Ahead of the 2025 elections, Friedrich Merz, the lead candidate of the CDU, broke a longstanding political taboo when his proposal to tighten asylum policies narrowly passed in the Bundestag with backing from the AfD. Meanwhile, German media have increasingly treated AfD representatives as legitimate political contenders.

Once marginalised in political debates, they are now regularly invited to talk shows. And they have received international legitimacy from figures such as US vice-president J.D. Vance, and X owner Elon Musk.

This election may give an indication of how far the AfD’s normalisation will go and how it will affect Germany’s political future. Beyond electoral success, the main question will be to what extent mainstream parties will incorporate far-right ideas in their political agenda.

What is already clear, however, is that the political landscape has shifted. The boundaries that once kept the far right at the margins are no longer as firm as they once were.

This article has been updated to include the results of the election exit poll.

Léonie de Jonge, Professor of Research on Far-Right Extremism, Institute for Research on Far-Right Extremism (IRex), University of Tübingen and Rolf Frankenberger, Managing Director Research, Institute for Research on Far-Right Extremism (IRex), University of Tübingen

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.